Utilitarianism, Fish and Science

By Dr. David E. W. Fenner

|

|

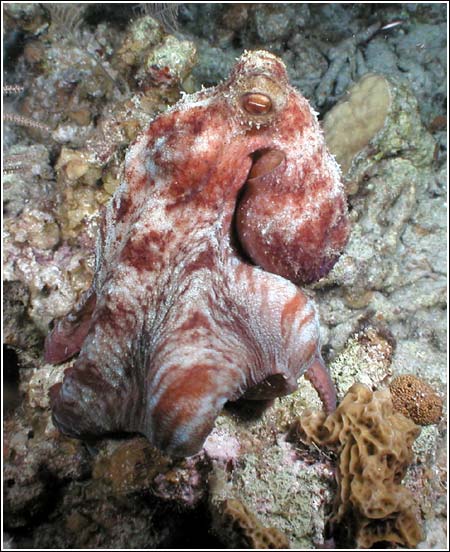

Bonaire Reef

Photo by Sonya

Tittle

|

The two most important animal rights theorists of the twentieth century were Peter Singer and Tom Regan. Singer wrote the highly influential book, Animal Liberation (Avon, 1975). Regan wrote The Case for Animal Rights (University of California, 1983). Singer and Regan also co-edited a very popular textbook called Animal Rights and Human Obligations (Prentice Hall, 1976). While Singer is frequently referred to as an “animal rights” theorist, this is not precisely true. Regan talks about animal rights. Singer simply talks about human obligations in respect of the moral standing of animals. Singer’s argument for why we should treat animals in particular ways – and refrain from treating them in others – is probably the most popular argument for ethical vegetarianism that has ever been put forward. I want to look at Singer’s work here, but before I do that, I want to talk about the background of arguments like his.

Singer is a good, straightforward utilitarian. At least this is clearly the case in Animal Liberation. Utilitarians believe that what one should do is to maximize utilities. A utility is anything that serves you. If you are a capitalist entrepreneur, then your utilities are profits and longevity. You want your business to make money, and you want this to happen over the long haul, not merely in the short term. If you are a student, then your utilities are credits and quality points. You need a certain number of course credits to graduate, and you need the highest GPA you can get – the best grades you can achieve – in order to get into the grad school of your choice, to impress a potential employer, or just to give your mom and dad something to brag about. If we are talking simply about ethics, the utility one is trying to maximize is goodness or value.

|

|

Cayman Angel

Photo by Sonya

Tittle

|

This is where the famous nineteenth century utilitarians – Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill – began. Though Bentham (who came before Mill) was interested in maximizing goodness, he was stuck with a problem. If one wants to maximize a thing, one first has to be able to measure it. If a thing is not quantifiable, then it is difficult to make sense of trying to maximize it. So Bentham made a move that we today identify as the core of contemporary utilitarianism; he said that the greater the amount of pleasure an action produced, the better (“more good”) that action was. The more pain an action produced, the worse (“more bad”) it was. This is the soul of what we call “hedonic utilitarianism,” and Mill echoes this in his “greatest happiness principle.” The reason Bentham thought this correlation between goodness and pleasure was legitimate is simple: he asked, “What do people value?” And the answer came back to him: “Pleasure.”

Bentham’s strategy is an excellent one because pleasure is clearly measurable (so long as the original correlation of pleasure and goodness holds, that is). Today, our measurement of pleasure would probably take the form of building a machine that could sense electro-chemical activity in the central nervous system. The more electro-chemical activity, the more pleasure there is; the more pleasure, the more goodness. But back in Bentham’s day, this would have been the stuff of science fiction. So he invented the “Hedonic Calculus,” a system of seven categories through which one could get a reading of how much pleasure (and pain) an action would produce. The seven categories were (1) the intensity of the pleasure, (2) the duration of the pleasure, (3) the purity of the pleasure – that it brought with it as little pain as possible, (4) the proximity of the pleasure – the closer the pleasure, emotionally, geographically, etc., the better, (5) the probability of the pleasure – the less risky the pleasure, the better, (6) the fecundity of the pleasure – that the pleasure would lead to still more pleasure, and (7) the “social extent” of the pleasure – that everyone affected by the action would have his pleasure and pain accounted for in the calculation. One would get a number in each of these seven categories, and if the number were on the positive side, the action would be pursued. If it were negative, indicating that there would be greater pain than pleasure, the action would not be pursued. (Essentially in all hedonic theories, the avoidance of pain is primary, and the acquisition of pleasure, secondary.)

Each of the seven numbers is given equal consideration with the others. However, if there is a “first among equals,” it’s number seven: social extent. It is very important to understand that the formula with which Bentham is working is not “goodness equals my pleasure.” It’s (basically) “goodness equals pleasure.” So everyone affected by the decision, everyone within the “sphere of influence” of the decision, gets a vote. Not a literal vote, of course. But everyone’s pleasure and pain are taken into account, to the furthest possible extent.

|

|

Cayman Reef

Photo by Sonya

Tittle

|

But look at the formula once more: “goodness equals pleasure.” The formula is not – and here we’re getting to the heart of the matter – “goodness equals human pleasure.” The formula is just about pleasure. All pleasure. Any kind of pleasure. Felt by anything that can feel pleasure. So animals – at least those for which we have some evidence that they can feel pleasure and pain – get votes!

This is the basis for Singer’s work and one that had a huge impact on Regan’s. Bentham is widely credited as being one of the first “animal rights” theorists (although, again for the sake of

|

|

Chain Moray

Photo by Sonya

Tittle

|

precision, Bentham does not talk about “rights,” just about proper treatment; for those interested in the detail, Bentham wrote this up in his Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, 1789, ch. XVII). Now we can turn to Singer and Regan. Peter Singer writes:

Many philosophers have proposed the principle of equal consideration of interests, in some form or other, as a basic moral principle; but . . .not many of them have recognized that this principle applies to members of other species as well as to our own . . . Other animals have emotions and desires and appear to be capable of enjoying a good life . . . Surely every sentient being is capable of leading a life that is happier or less miserable than some alternative life, and hence has a claim to be taken into account. In this respect the distinction between humans and nonhumans is not a sharp distinction, but rather a continuum along which we move gradually, and with overlaps between species, from simple capacities for enjoyment and satisfaction, or pain and suffering, to more complex ones (“All Animals are Equal" in Animal Rights and Human Obligations, pp. 78 and 82).

|

|

Chaz and

turtle Photo by

Sonya Tittle

|

And Tom Regan writes:

Pain is pain wherever it occurs. If your neighbor's causing you pain is wrong because of the pain that is caused, we cannot rationally ignore or dismiss the moral relevance of the pain that your dog feels . . . We are each of us the experiencing subject of a life, a conscious creature having an individual welfare that has importance to us whatever our usefulness to others . . . Ands the same is true of those animals that concern us (the ones that are eaten and trapped, for example), they too must be viewed as the experiencing subject of a life, with inherent value of their own ("The Case for Animal Rights" in Animal Rights and Human Obligations, pp. 106 and 111-112).

Do we believe that animals other than human ones feel pleasure and pain? “Sentience” means “capable of experiencing sensation.” Do we believe that there are at least some nonhuman animals that are sentient?

The burden of proof, I think, really rests with those who say that the only sentient being is the human one. The evidence that dogs, cats, horses, cows, chickens, and raccoons feel pleasure and pain is just too obvious. They pull back and emit sounds – just like we do – when they are subjected to events that would put us in pain. They have central nervous systems – just like we do. If both the behavior and anatomical evidence suggest that they feel in a way similar to the way that we feel, then the burden of proof that no animal other than the human one feels pleasure and pain is on the person advancing that claim.

But now we have a new problem. Do all nonhuman animals feel pleasure and pain? Do marine mammals? Do fish? Do mollusks?

I have a friend in Miami who is a staunch ethical vegetarian, and he takes this path because of arguments like those of Singer, Regan and Bentham. My friend takes seriously the call to not inflict pain on those creatures capable of feeling it. And so while he does not eat the flesh of cows, chickens, or fish – believing fish to be sentient – he does eat shrimp. He draws the “sentience line” below fish but above mollusks. I asked him once if he ate lobster. His first response was, “Not on a teacher’s salary.” But his second response was, “I would, because we do not have good evidence that lobsters can feel pleasure and pain.” I had a follow-up question: “Don’t they say that when you drop live lobsters into boiling water, that they scream?” He answered, “Yes, but

|

|

Cayman Angel

Photo by Sonya

Tittle

|

apparently that noise is air escaping from their bodies.” “Yes,” I replied, “but when you scream, isn’t that air escaping from your body?”

This is a problem. Where do we draw the sentience line? If we do not draw such a line, what is to prevent someone from arguing that we ought not eat plants, because they are living things, too, and, “Who are you to say that they don’t feel pain?” This is too far. Except for fruits and vegetables already fallen from plants, “stolen” milk, and “stolen” honey, there is nothing for us to eat that is not, or was not once, alive. So we must draw a line somewhere along the continuum of life.

|

|

Cayman Angel

Photo by Sonya

Tittle

|

My title is “Utilitarianism, Fish, and Science.” We

have already discussed utilitarianism, and I have just now raised

the “fish problem.” Now we turn to science. What is

sentient, and what is not, is not an opinion question. It is not an

arbitrary matter, and it cannot be solved through philosophical

speculation. The line involves citing a fact. And that fact is one

which only good science can deliver. Whether this short article is

advocating ethical vegetarianism is something the reader will have

to decide. But clearly what we learn from Regan and Singer is that

our ethical concerns must encompass more than human considerations.

And now it is time to do our homework to learn, from science, the

proper range of those appropriate concerns.

|

|

Cayman Angel

Photo by Sonya

Tittle

|

Copyright ©2002 Global

Underwater Explorers.

All rights reserved.